Pantheon.

Pantheon.

Carlos Vilares: The main challenge is that private markets are by their nature more illiquid and require capital to be locked up for longer periods, for which investors are hopefully rewarded in the form of premium returns. Most structures, albeit not all, follow a similar model that revolves around some form of closed-end fund, which has a set life that can be from five to 25 years depending on the asset class. Most private equity fund lifespans are around 10 years, debt funds are six to seven years, while infrastructure funds tend to be set in the mid-teens.

The fundamental issue around liquidity is that the assets or the loans that an investor is buying exposure to are not traded on a liquid market. But the reality is that even liquid stocks aren't necessarily liquid when you need cash because every investor could need cash at the same time – and we’ve seen the issues that can cause. That's the challenge faced by hedge funds and other similar vehicles.

Francesco di Valmarana: A second issue is the drawdown model. In most public markets, if you want to invest $10m you send that money to the manager and buy the market, effectively today. But private markets vehicles are different: you can have the best offer – with parameters around it – but you commit to providing the investors with $10m over a period and they will ask for the capital as they find the transactions. These vehicles also don’t provide the cash flow back immediately, as it takes time to generate yield.

"If markets fall, listed assets tend to be more reactive,

which can decrease the value of the portfolio."

That creates two problems. One is for the fund managers, or general partners, who have to be confident that an investor is good as a counterparty and that two years hence they will be in a position to provide the capital requested. From an investor perspective, you have contingent liabilities in the form of uncalled commitments and, as you build a programme, you are going to have more stacking up. That means for most investors they can continually tune the target level of exposure they would like to private markets, which will typically be above their actual level of exposure at any given time.

However, if markets fall, listed assets tend to be more reactive, which can decrease the overall value of the portfolio and increase the share represented by less volatile private market assets. This is called the ‘denominator effect’ and can lead to the reverse situation where the actual allocation to private markets is above the target allocation. In that situation investors either have to hold their nerve, increase the target allocation – or rebalance the portfolio.

Francesco: Insurers, depending on their authority, have two issues. One is using some form of matching to align the duration of their liabilities with that of their assets. Then there is capital charge, for which the calculation is straightforward: on debt assets, for example, it's the risk of the asset multiplied by its duration. Illiquidity increases that duration element of the equation.

"The real beauty of the secondary market in the context

of insurers is that it reduces the duration element of the calculation."

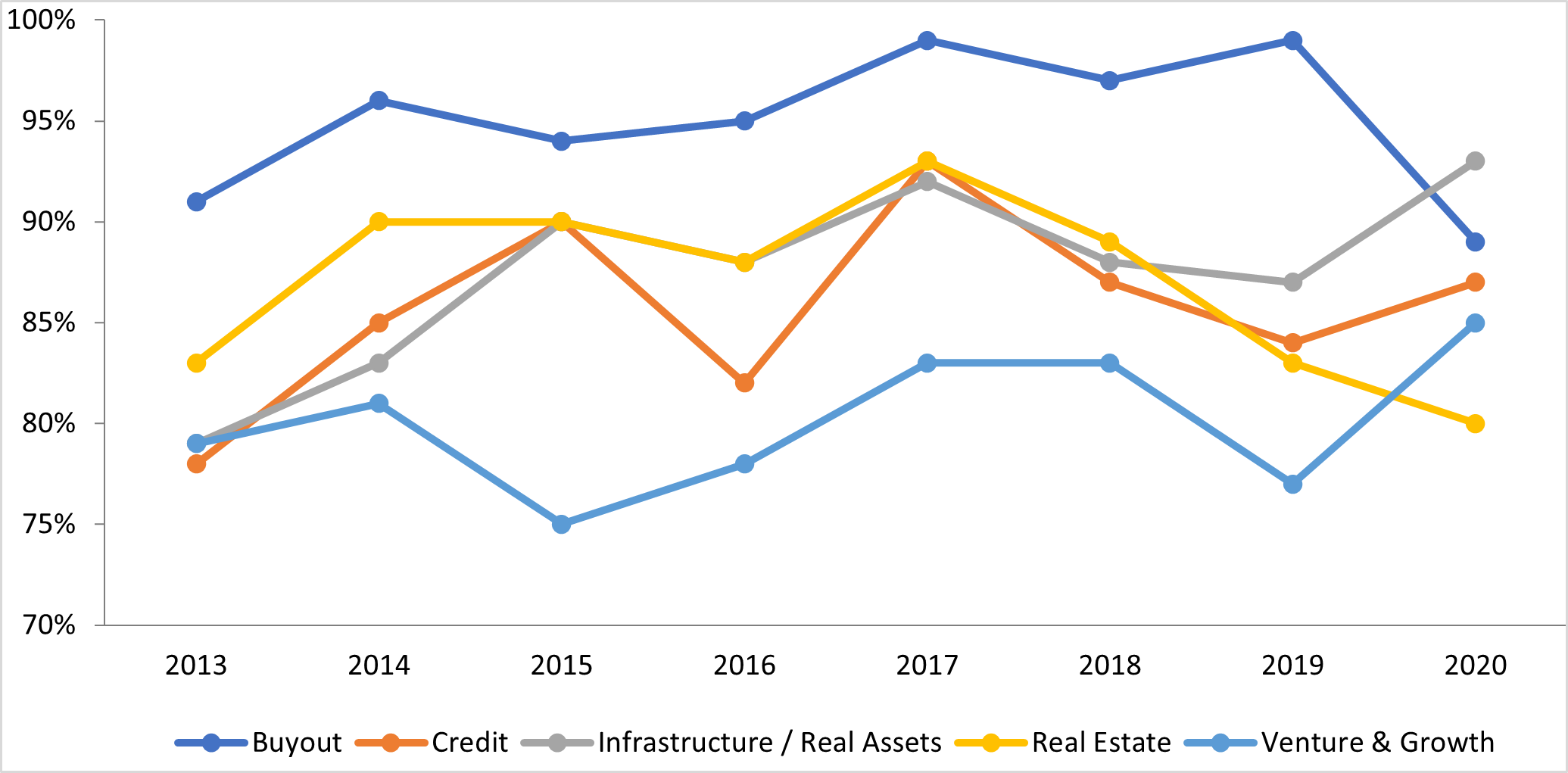

One potential solution is the secondary market, which is used to sell and buy existing positions or assets in private market funds. In a traditional secondary deal, the buyer is taking on the existing share of the fund, as well as the liability for any uncalled commitments. They can see the assets they are buying, or at least a good portion of them, and will often be able to buy at a discount (see figure 1) so, if the assets are performing, they can potentially benefit from immediate uplift.

The real beauty of the secondary market in the context of insurers is that because the fund is already some way through its life and money is in the ground, it reduces the duration element of the calculation – and also reduces the time to distributions and the overall cost of the exposure. For sellers, the secondary market offers a valuable liquidity solution for those who need to rebalance or who are looking to manage their portfolio, and that are willing to give up some of the potential upside on the assets.

Figure 1: Historical secondary pricing as a % of NAV. Source: Greenhill, Global Secondary Market Review 2021.

Carlos: Part of the issue with private markets, as noted, is that these closed-end fund structures mean insurers are asked to tie up their capital for between seven to 10 years or more, plus potential extensions. We also have to consider the liquidity demand on the liabilities. A general insurer tends to have unpredictable liabilities and liquidity could be needed at any time, while with-profits funds on the life insurance side have additional demands on capital too. All of this means that although high liquidity isn't always required, there is a need for a degree of flexibility that is often exacerbated in times of stress.

For most general insurers, the answer until now has been to resist long capital lockups. Increasingly, however, the secondary market in private funds is one mechanism for providing liquidity without having to forfeit altogether the potentially premium returns that can be accessed. Also, by buying mature assets in the secondary market, you are buying into assets that are already returning capital and income.

Francesco: Let’s take the simple example of using the secondary market to buy into an existing fund that is fully invested. You are buying an asset that has a shorter duration to maturity, because it is already halfway through its life and the money is already invested, which helps with cash flow and liquidity. Some of the assets in the portfolio will already be producing distributions, or will do so quickly, which also mitigates the so-called J-curve that you typically see on a private equity fund, where returns are negative in the first year or two while fees are charged and there no returns.

"In a secondary fund, instead of buying a seven-year

loan you are buying a three- or four-year loan."

Carlos: For insurers, the capital charge aspect is also helped. Take for example a private debt fund, where the capital charge an insurer must take on the underlying the private debt asset is based on a combination of the duration and the credit quality. In a secondary fund, instead of buying a seven-year loan you are buying a three- or four-year loan, so you will have half of the capital charge for those assets. And of course, all of that is before you consider the broader benefits of investing in a portfolio that you can see and underwrite at outset and that is often more diversified, rather than taking on the ‘blind pool’ risk of investing in a primary fund that is yet to make commitments.

Carlos: Rates going up isn’t necessarily an issue because the market was in a situation where real rates have gone down as inflation has risen at a much faster rate. That environment makes fixed-income even less attractive and the impetus to find a higher-yielding asset even greater. That’s where private markets come in and why they have been growing as a share of the investible universe, even during more benign periods of the economic cycle.

"The secondary market mechanisms have been

around for a long time in private equity."

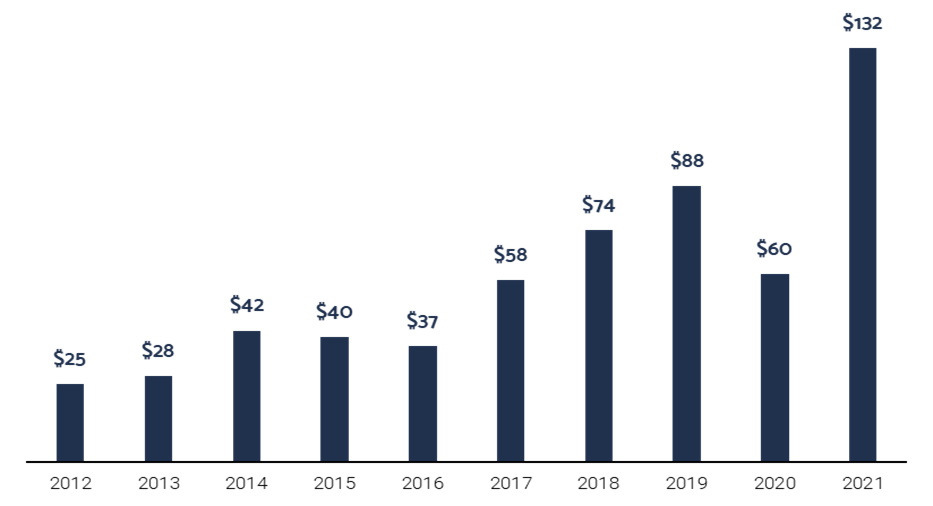

Historically, one of the drivers for selling into the secondary market has been private market assets have performed stronger than public market assets, so a seller could book decent returns even if they eventually sell a portfolio at a discount to latest portfolio value. Between that and the demand from buyers, the size of the market has grown hugely over the past few years and last year was estimated to be $130bn, with projections of it getting to $200bn in the next year or two (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Secondaries Transaction Volume ($bn). Source: Source: Jefferies Global Secondary Market Review, January 2022.

Francesco: You have to remember that the secondary market mechanisms have been around for a long time in private equity, where they took 15 years to become an established part of the market. It was still viewed as a backwater from the mid-1980s until around the 2000s and then took off – and it continues to grow now. Then factor in the growth in infrastructure secondaries, which started after the Great Financial Crisis and have now become mainstream, followed by the emergence and rapid scaling up in the past two to three years of the secondary market in private debt.

Overall, it feels like there is a lot of growth ahead and there is a great deal of innovation and product evolution going on, so there will be opportunities for investors – and, given the wider market environment, in the next year or so some quite favourable pricing.