Patrick Saner, Head Macro Strategy, Swiss Re Institute and Fiona Gillespie, Macro Strategist, Swiss Re Institute explain why monetary easing is the main catalyst of the divergence between macro and markets.

While Q2 was an even sharper contraction than Q1, this year's first quarter trough in risk assets seems nothing but a distant memory. US stocks and bonds have rallied since the end of March.

The disconnect between the economy and financial markets is particularly pronounced in the current COVID-19 crisis, but there has been divergence in asset prices and the real economy since the time of the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008-09.

This can be explained by several factors. Even so, in the here and now we continue to see downside for risk assets: the economic environment is set to remain challenging for a while yet, putting downward pressure on corporate earnings.

"The disconnect between the economy and financial markets

is particularly pronounced in the current COVID-19 crisis."

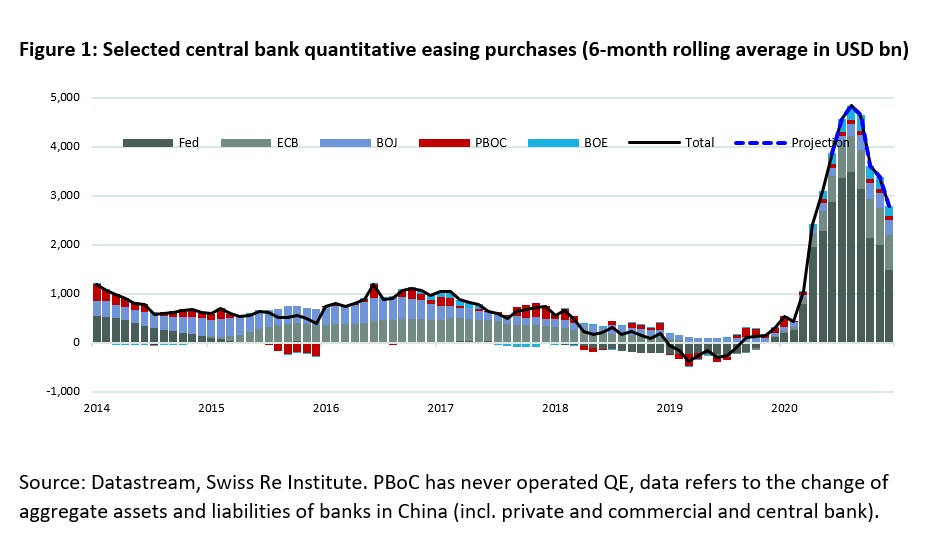

Monetary easing is a main catalyst of the divergence. Central bank actions can and do support financial markets, but they are less effective in stimulating the real economy.

This holds particularly true in these unprecedented times, when consumer spending is fundamentally constrained by lockdowns.

In rapidly unveiling its playbook from the GFC, the Fed provided much needed liquidity support. However, the announcement that the Fed would become active in the corporate bond market also spurred record levels of debt issuance.

Higher debt issuance along with the fiscal measures is leading to a rise in corporate leverage. Years of record low interest rates have not only fuelled strong growth in the corporate bond sector since 2007, but also a deterioration in credit quality.

"Central bank actions can and do support financial markets,

but they are less effective in stimulating the real economy."

We believe the increase in credit to bridge the downturn, combined with a protracted economic recovery leaving earnings under pressure, will expand the debt burden.

As such, we anticipate actual defaults will rise even if spreads move sideways or tighten further.

Credit will become particularly exposed to downside risks if Fed purchases prove unsuccessful in providing a sustainable backstop.

However, the vast purchase programs from major central banks are a clear positive "game changer" for the corporate bond market.

The second reason for the disconnect is that financial markets are typically forward-looking, whereas economic releases tend to look backwards.

At the most fundamental level, a company's share price should be a reflection of future earnings.

While near-term earnings may correlate with a country's economic growth, the value of a stock looks beyond current developments to discount future earnings expectations.

On 23 March 2020, the Atlanta Fed reported that US firms were bracing for a massive contraction in sales as a result of developments surrounding COVID-19.

This coincided with the trough in the US stock market, which had fallen by more than 30 per cent since the start of the month.

"The second reason for the disconnect is that financial markets are typically

forward-looking, whereas economic releases tend to look backwards."

By end-April, the equity market had retraced more than 80 per cent of those losses, despite US companies expecting even larger impacts from COVID-19 on their revenues.

This apparent disconnect may point to equity investors looking beyond the immediate collapse in broad fundamentals in anticipation of a relatively rapid rebound in activity.

Corporate credit investors seem to share the same view: the implied default probability of the US IG market has more than halved from the wides of March.

While central bank support is containing spread risk, actual defaults will still rise as companies struggle to remain solvent. This makes sector allocation key.

"While central bank support is containing spread risk,

actual defaults will still rise"

Last but not least, a country's financial market is not a reflection of its economic composition.

Economic output can be measured by the aggregate expenditure which translates into revenues for companies. As such, one may expect a relationship between equity returns and economic growth.

In reality, however, there are important differences between the stock market and the economy. In the US, for instance, smaller firms have little stock market presence despite representing 44 per cent of the economy.

In contrast, the five largest US companies make up 20 per cent of stock value, but only 4 per cent of national gross domestic product (GDP).

"A country's financial market is not a reflection of its economic composition."

Globalisation has allowed large firms to diversify their revenue streams, and the five largest get nearly 50 per cent of their revenues from exports. However, exports represent less than 12 per cent of GDP.

Although international revenue diversification is unlikely to noticeably mitigate domestic headwinds given the global nature of the COVID-19 shock, our expectation for a multi-speed recovery across key economies might deliver overseas support to large US firms at a time when domestic demand is weak.